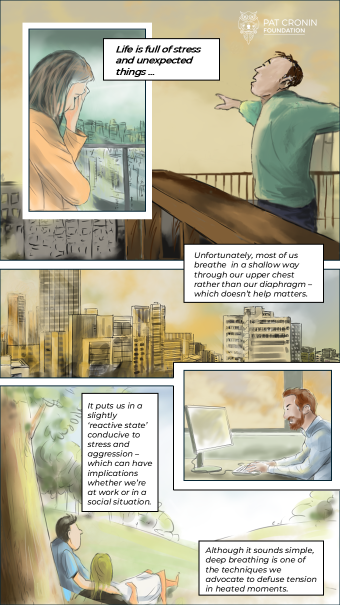

Breathing is something we do around 22,000 times a day. With that much practice, you’d think we’d all be experts – but not quite.

In fact, many of us breathe in ways that fuel stress rather than alleviate it.

The good news? With a bit of practice, we can all learn to breathe more effectively and pick up a skill that can help not all alleviate stress but help defuse arguments and conflict.

At the Pat Cronin Foundation, our presenters emphasise the power of deep breaths to help calm down in tense or aggressive situations – a notion backed up by experts in the field such as Monash University’s Shawn Ashkanasy.

The way we breath can influence how we feel and react.

Ashkanasy, a PhD student at Monash Business School, is conducting research into how specific breathing techniques can help regulate emotions and improve decision-making in high-stress environments, including the workplace.

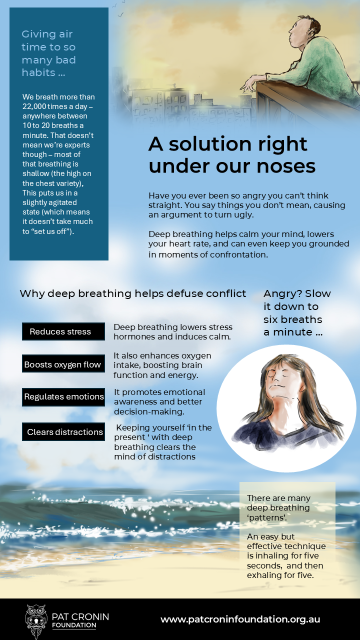

He focuses on “slow-paced breathing” (SPB), a method of breathing six times a minute, where the inhalation is slightly shorter than the exhalation.

While precise timing isn’t crucial for most of us, the principles behind this technique can have a powerful effect on calming the mind and reducing stress.

Ashkanasy’s research highlights an important fact: the way we breathe can influence how we feel and react, especially in tense situations.

As he explains, “Breathing does matter, and if we become aware of how we are breathing, we can actively play a role in changing those patterns for the better.”

His study, which will involve over 100 participants, aims to demonstrate how even minor adjustments to our breathing can improve stress resilience and cognitive performance.

Two things are key here:

- Shallow breathing: Most of us breathe shallowly through our upper chest rather than our diaphragm, which can keep us in a slightly “reactive” state, conducive to stress and aggression

- Reinforced bad habits: Since we breathe so often, poor breathing patterns become ingrained without us realising it

Why it works: The science behind deep breathing

When faced with a confrontation, the body’s natural “fight or flight” response kicks in. This response, controlled by the sympathetic nervous system, floods the body with stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol, causing increased heart rate and rapid breathing.

While this response is useful in life-threatening situations, it can be counterproductive in everyday conflicts, often escalating rather than calming the situation.

Deep breathing, however, activates the parasympathetic nervous system—the “rest and digest” counterpart to the stress response.

By consciously slowing down your breath, you signal to your brain that it’s safe to relax. Some studies show that taking slow, deep breaths for just 90 seconds can significantly reduce levels of cortisol, the primary stress hormone.

This simple act can be a powerful tool in calming yourself and defusing tension in heated moments.

According to Foundation presenter Peter Kennedy: “In the second of our two presentations (“Rethinking Anger”), we talk a lot more about the techniques, including deep breathing, to bring someone’s stress levels down.

“And that includes having the breath from deep within your diaphragm rather than just high on the chest.

“If we don‘t teach people how to bring their anger and their stress levels down, how do we expect to impart change.

“Just one of the elements we talk about is how to breathe, in a better sense, and how to allow yourself to think more clearly and defuse a situation.”

Breathing new life into workplace wellbeing

Ashkanasy’s specific research will test the effect of “slow-paced breathing” (breathing about six times every 60 seconds for up to 20 minutes) on the heart rate, stress resilience and cognitive performance.

A pilot study is under way at the Monash Business Behavioural Lab, with a larger one planned for 2025.